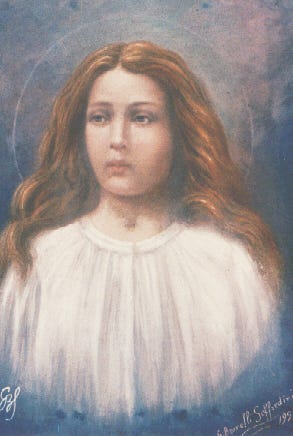

In defense of Saint Maria Goretti’s martyrdom

On July 6, the Church commemorates a different sort of virgin-martyr: Saint Maria Goretti (1890-1902). Unlike the great virgin-martyrs of the early Church—Saints Agnes of Rome, Apollonia of Alexandria, Margaret of Antioch, to name a few—Maria Goretti was not ordered by pagans to renounce her faith or face death. Instead, she died because she resisted sexual assault.

Of course, Maria’s biography makes everyone uncomfortable because the circumstances of her death are painful to relate. Rape victims may wrongly assume that the Church is using Maria’s example to encourage women to fight back against their assailants or to blame those victims who did not. Some feminists reinterpret her story in an unfavorable light based on their understanding of power and patriarchy.

But Maria’s story is not about rape. Rather, it is about holiness and about imitating Jesus Christ.

Maria was the third of her parents’ seven children and was born in Corinaldo, Italy. Her parents couldn’t make enough money to feed their children on their farm, so they moved to Nettuno. There they farmed the land and shared their home with a man named Giovanni Serenelli, along with his son Alessandro.

Maria’s father died when she was nine years old. To help feed the family, Maria’s mother worked in the fields, while Maria stayed home to care for the household and her baby sister.

On July 5, 1902, Alessandro left the others as they were working in the fields and returned to the home, where he knew Maria would be alone. He asked her to follow him into the house. When she refused, he dragged her inside. He tried to convince her to have sexual intercourse with him. When she said no, he stabbed her repeatedly and locked himself in his room.

When Maria was found, she was still alive, but she had lost too much blood to survive. She died in a hospital twenty-four hours later.

Although Maria’s death was certainly tragic and her murder moved the hearts of people all over Italy at the time, the above details alone would not have been sufficient to canonize her. However, there is much more to Maria’s story.

During those twenty-four hours while she lay dying, Maria acted like a saint. She worried about where her mother, who stayed by Maria’s bed all night, would sleep. She bore a long surgery, performed without anesthesia, with patience. She admitted to her mother that Alessandro had tried to pressure her in the same way on two previous occasions, and she had strongly rejected him. (She was old enough to realize that her family needed help from the Serenelli men to make ends meet, which is probably why she had not told her mother prior to the final attack.) She received the sacraments for the last time like the innocent child that she was. When the priest asked Maria if she forgave her murderer, she told him yes, and she said she wanted Alessandro to be in Heaven with her.

Of course, this amazing display of Christian virtue and forgiveness did not occur out of the blue. Maria had always been a devout child, had taught her younger siblings to pray, and had made sacrifices to attend classes so that she could receive her First Holy Communion with those her age.

However, as often happens with the saints, the impact of Maria’s holy life did not end with her death.

Alessandro Serenelli was arrested immediately by the police. He admitted his crime but showed no remorse. After a widely publicized trial, he was sentenced to thirty years in prison. He was ordered to spend the first three years in solitary confinement and the remainder in hard, monotonous labor.

In December of 1908, an earthquake struck the region where Alessandro was imprisoned, and 30,000 people in a nearby city died. The prisoners, however, were spared, which made some of them think about God and His mercy.

A few days after the earthquake, Alessandro had a dream. In the dream, his cell became a garden, and a beautiful girl dressed in white came toward him. He recognized Maria, and he was terrified. But Maria carefully placed white lilies, one by one, in his hand: fourteen lilies, one flower for each of the stab wounds he had inflicted on her to end her life.

After that dream, Alessandro was a changed man. For the first time, he was sorry for what he had done, and he wept for his sins. He became a model prisoner and was released after twenty-seven years in prison.

However, as an infamous murderer, it was difficult for Alessandro to get or keep a job. He remarked to others that he found it more difficult to be an unemployed vagabond than a prison inmate. In 1937, some Capuchin friars agreed to give him a chance and offered him the position of porter in their friary. In addition to his duties, Alessandro participated in the community’s daily routine. He spent the rest of his life in the friary as a layman.

Neighbors noticed Alessandro’s simple life of prayer and repentance, and gradually they began to see him less as a monster and more as a man of penance. He died a peaceful death—although pestered by the news media to the end—at the age of eighty-seven. Years of penance and prayer had purified his heart, and some who knew him even called him a saint.

But there was at least one more person who was profoundly affected by Maria’s sanctity: her mother.

After Maria’s death, Assunta Goretti became the only source of financial support for her remaining children. Although she did her best, she eventually had to place her children in the care of others. Maria’s death literally destroyed Assunta’s family.

That’s why it is all the more surprising that when the freed and repentant Alessandro showed up on her doorstep in 1934, asking for her forgiveness, Assunta said yes. After thirty-two years of thinking and praying about Maria’s death, Assunta was able to simply tell Alessandro, “God has forgiven you, Maria has forgiven you, and I too forgive you.”[1] They demonstrated that reconciliation by attending Christmas Mass and receiving Communion together.

Assunta remained in contact with Alessandro for the rest of her life. Maria’s example of holiness had been publicly praised by popes, and her canonization process was begun. Alessandro agreed to testify about what happened on that fateful day—about how he killed a saint—at Maria’s canonization proceedings. His testimony was valuable evidence, helping to lead to her beatification in 1947 and her canonization in 1950.

Maria’s life of heroic virtue was probably sufficient proof for her to be canonized, but her peaceful acceptance of a brutal death made many people wonder if she should not be acclaimed as a martyr as well.

Fr. Mauro Liberati, the postulator of Maria’s cause for canonization, argued that she did die a martyr. He cited Saint Thomas Aquinas, who had stated that someone could be called a martyr if that person died for even one Catholic virtue. Clearly, Maria fit in that category. Another argument for Maria’s martyrdom could also be drawn from Saint Augustine of Hippo, who had written a letter to another bishop about the status of nuns who had been raped, a not uncommon tragedy in the ancient world. For example, if a woman is a consecrated virgin, does she lose her chastity if she is sexually assaulted? According to Augustine, “Violence cannot violate chastity if the mind preserves it. Even the chastity of the body is not violated when she who suffers is not voluntarily abusing her body but is enduring without consenting to what another is perpetrating.”[2] Regardless of the reasons, Pope Pius XII ultimately declared Maria Goretti to be a martyr.

By declaring her a martyr in defensum castitatis (in defense of chastity), the Church opened the door for the recognition of another kind of martyrdom: a person who is willing to sacrifice life itself for the sake of that virtue. Since then, several women have been declared martyrs and blesseds according to this criterion,[3] just like Maria. In each of these cases, the woman or girl in question was recognized for having lived a devout, chaste life. When she was threatened with sexual violence, she resisted to the point of death.

However, there is one more lesson to be found in young Maria’s refusal to commit the sin of fornication. At her canonization proceedings, Alessandro testified that during those final moments Maria repeatedly tried to warn him that by committing this sin, he would be endangering his own soul. Maria not only rejected the act as a sin, she cared about the salvation of her assailant.

In this way, Maria shows the heart of Christ and the mind of the Church in the matter of sexual assault. Rape is a mortal sin, one which could separate the perpetrator from God for all eternity. Maria knew this, and she was willing to lay down her own life rather than allow another person to commit a sin grave enough to deserve eternal damnation.

If only every Christian was as aware of the dangers of sexual sins as was eleven-year-old Saint Maria Goretti.

[1] Charles D. Engel, Alessandro Serenelli: A Story of Forgiveness (Huntingdon, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 2020), 49.

[2] Ibid, 61.

[3] The following women are now recognized as blesseds and died as martyrs in defense of their chastity during the twentieth century: Karolina Kozkowna (1898-1914) of Poland, Albertina Berkenbrock (1919-1931) of Brazil, Teresa Bracco (1924-1944) of Italy, Anna Kolesárová (1928-1944) of Poland, Pierina Morosini (1931-1957) of Italy, Veronica Antal (1935-1958) of Romania, and Isabella Cristina Mrad Campos (1962-1982) of Brazil.