A lifelong litany of humility

The holy and humble life of Servant of God Raphael Merry del Val

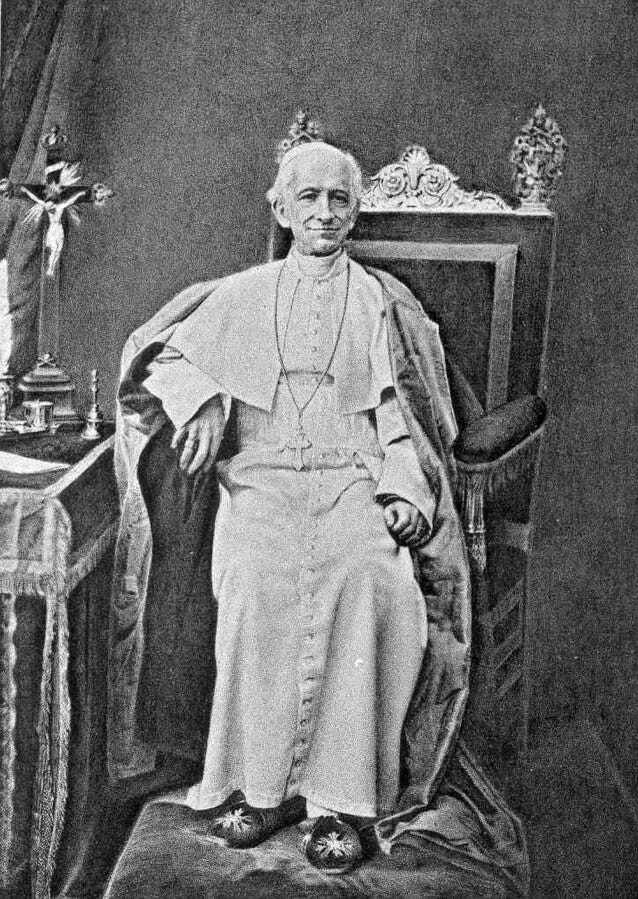

Many great saints have been born into poverty, chosen solitude, and lived in obscurity. But that is not the only way to become holy, as is shown in the life of Servant of God Rafael Merry del Val (1865-1930).

The first thing one must understand about Rafael Merry del Val is his name. His full name is a mouthful: Rafael Maria José Pedro Francisco Borja Domingo Gerardo de la Santisma Trinidad Merry del Val. But “Merry del Val” is his last name. After all, his father was Rafael, Marquis of Merry del Val, an accomplished diplomat who could count French crusaders, members of the Spanish nobility, and Irish merchants among his ancestors. His mother also had a noble Dutch, Scottish, and Spanish heritage. While both parents were wealthy and traveled in powerful social circles, they were also devout Catholics. Rafael’s mother, unlike most women in her position, took a personal, daily interest in the upbringing of her five children, particularly their faith in God. It was probably due to her influence that “Francisco Borja” was tucked into the name of her second son, precisely because he was born on the famous Jesuit’s feast day.

Rafael had an ordinary, happy childhood in many ways. He was close to his siblings, even though his brother Pedro frequently teased him about not being able to keep his room neat. Rafael was born in the Spanish embassy in London, considered himself an Englishman despite his international heritage, and attended the best schools. He was an excellent student, but he was also cheerful, manly, friendly, unapologetically pious, and loved sports.

No one was surprised when he decided to become a priest. His personal goal was to enter the Pontifical Scots College in Rome, be ordained to the priesthood, and return to England. He hoped to spend his life as a simple parish priest and bring many of his countryman back into the Church. But the pope had other plans.

When Rafael first came to Rome with his father to enter the seminary, he was formally introduced to Pope Leo XIII. The pope took one look at the tall, accomplished twenty-year-old seminarian and changed the course of his life. Leo XIII decided that Rafael should instead study at the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy. Both Rafael and his father were shocked, recognizing that this would put him on the fast track for advancement in the Church hierarchy and probably keep him in Rome, not England, throughout his priestly career.

After Rafael had been ordained a priest—and earned a couple of doctorates and a licentiate, as well as being ordained bishop—something similar happened during the consistory to elect a new pope in 1903. At the time, Rafael was acting as secretary of the conclave, and he went looking for a leading candidate, Cardinal Giuseppe Sarto, for a practical reason. When he found Sarto, Rafael, who was a sensitive man, recognized that the kneeling, weeping cardinal was praying not to be elected pope. Rafael encouraged him, reminding him that our Lord would be with him. Clearly Sarto recognized something in Rafael because only few months later, as Pope Pius X, he named the thirty-eight-year old bishop to become his Secretary of State.

There was an uproar when Pius selected such a young priest to be, essentially, the prime minister of the Holy See. Throughout Pius’ papacy, the press frequently caricatured Pius X as a simple country priest, trying in vain to deal with complicated matters and far out of his depth, while portraying Secretary Merry del Val as the scheming planner behind of all the pope’s controversial decisions.

Fortunately, over time, the world came to recognize the truth. It was Pius’ holiness, wisdom, and Christ-like strength which enabled him to bravely stand his ground against people—both inside and outside of the Church—who denigrated or endangered Church teaching about truth, morality, and the practice of the faith.

In retrospect, it is easy to understand why Pius X chose Rafael for such an important and sensitive position. Rafael had been raised in the complex world of the aristocracy and politics, although he personally shunned high society and never attended events that were not directly required by his duties. He also flawlessly spoke multiple languages: English, Latin, Spanish, French, and Italian. This enabled him to personally read documents and negotiate with leaders from different countries.

But his language skills also helped him to assist people from all over the world during his day-to-day duties with the pope. For example, during one public papal audience, an Irish nun who was on pilgrimage in Rome with her novices carefully addressed the pope in Italian. When the pope replied to her in Italian, the nun, who had exhausted her entire knowledge of Italian in her speech, flushed with embarrassment. Fortunately, Cardinal Merry del Val saved face for all those present by quietly speaking to her in English and translating for both her and the pope.

Pius X has been named a saint for his personal holiness. His actions as Chief Shepherd of the Church, such as his identification of the errors of Modernist heresies and his reform of the liturgy, canon law, Church administration, and even the age of reception of First Holy Communion, have had long-lasting impacts on the Church. Rafael was always the pope’s right hand man and strong supporter. Although Pius X and Rafael came from very different backgrounds and were far apart in age, they shared a deep friendship rooted in their profound love of Jesus Christ, allowing them to be very effective in their work in service of His Church.

Pope Pius also made many important decisions in terms of Church-State relations. In these complicated matters, he was greatly aided by his like-minded secretary of state. One could say that Pius was so successful in part because his secretary of state “always had his back.” For example, they both recognized a devastating war was on the horizon. Trying to prevent that war, Cardinal Merry del Val carefully negotiated and signed a concordat with Serbia in 1914. Sadly, four days later, this successful step toward peace disappeared when archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, plunging the world into World War I.

One of the most controversial decisions made during Pius’ reign was his refusal to accommodate the liberal demands of the French government. Today, this decision is still criticized. It is commonly assumed that Pope Pius needed to “get with the times,” accept a complete separation of the Church from the State, and eliminate the traditional alliance between the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. And it is true that Pius’ refusal to accept the terms of France’s secular government bankrupted the Church in France.

But it also true that France’s 1905 Law of Separation was not a benevolent “live and let live” separation of the French government from Catholicism. Through this law, the French government took ownership of church property, banned religious symbols in public places, forbade religious instruction in state schools for children, and penalized ministers who made “seditious” statements in church. It is not surprising that atheistic Masonic organizations were the not-so-hidden supporters behind this legislation. One can see the bitter fruit of these measures a century later as entire countries have become accustomed to the silencing of Christians and Christianity in the public sphere.

After Pius’ death, Rafael grieved the loss of a pope, but also the loss of a man he had come to think of as a second father and a friend. Pius’ successor, Benedict XV, named Rafael as Secretary of the Congregation of the Holy Office, which was an important position but generally seen as a demotion. Although Rafael was present for two papal conclaves as a cardinal, he never held such a high office again.

But he did not care. The man who had hoped to be a simple parish priest and who hated the shallowness of social events did not pine for the spotlight. Instead, those who knew Rafael later gave witness about many signs of holiness in his personal life.

For example, in private Rafael wore a worn cassock, lived very simply, and quietly accepted without comment whatever food he was served. When celebrating Mass for the King of Kings, however, he insisted on offering only the best and was a model of recollection and serenity. He served as a spiritual director to people of all backgrounds, treating each person as if he or she were the most important person at the moment, even when his waiting room was full to overflowing. He personally adopted the working-class Trastevere neighborhood of Rome, visiting it every week and forming genuine friendships with the families there, particularly the boys. Yes, one of the most powerful cardinals in Rome spent his free time like a simple parish priest, talking to poor boys about games, school, and their faith in God.

Then one day, unexpectedly, Rafael was stricken with appendicitis. His friends wept, and the doctors said his case was hopeless. Witnesses related that he was completely at peace the entire time, never complained despite the severe pain, and continued to calmly pray. He calmly accepted the doctor’s decision to attempt a last-minute operation without anesthesia, but he died on the operating table on February 26, 1930.

Although he wanted to be buried very simply near Pope Pius X, the Spanish government donated Spanish marble to honor him with a beautiful tomb. He left behind many writings, including personal letters, prayers, rule of life, and letters of spiritual direction. Tragically, a fire in the study of Rafael’s personal secretary later destroyed many of his writings. It is possible, though not easy, to find biographies and collections of his writings today.

Why is it that such a holy man is still only recognized as a Servant of God by the Church? Some say that, although more than a century has passed, the French government and others still bitterly resent his actions as secretary of state. Perhaps he is still overshadowed by the saintly pope, Pius X. Or perhaps, lacking a religious congregation willing to promote his cause, he has simply been forgotten.

But that could change. His most famous prayer was one that he composed himself and prayed every day after Mass. If more people pray Servant of God Rafael Merry del Val’s prayer, perhaps his reputation as a holy man will spread, which will reinvigorate the cause for his canonization. At the very least, it will remind us that God does not love people based on job titles, wealth, personal gifts, or even the names of our important friends. Instead, our entire lives can be a litany acknowledging our nothingness before God and our great love for Him.

Litany of Humility

Lord Jesus. Meek and humble of heart, Hear me.

From the desire of being esteemed, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being loved, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being extolled, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being honored, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being praised, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being preferred to others, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being consulted, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the desire of being approved, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being humiliated, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being despised, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of suffering rebukes, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being calumniated, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being forgotten, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being ridiculed, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being wronged, Deliver me, Jesus.

From the fear of being suspected, Deliver me, Jesus.

That others may be loved more than I, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That others may be esteemed more than I, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That, in the opinion of the world, others may increase and I may decrease, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That others may be chosen and I set aside, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That others may be praised and I unnoticed, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That others may be preferred to me in everything, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

That others may become holier than I, provided that I may become as holy as I should, Jesus, grant me the grace to desire it.

— Rafael Cardinal Merry del Val (slightly modernized version)

Excellent example of "...not I but Christ liveth in me"!

Thank you for such an encouraging summary of such a lovely saint.